Are older music technologies better at capturing ‘liveness’ in recordings?

by Dr Sue Miller

18 Jun 2020

Have contemporary technological changes in recording and the search for perfection been to the detriment of musical skills? Do today’s digital approaches create recordings that are too mechanical and lacking in the human touch? While older unedited recordings maintain their ‘liveness’ in the case of many Latin recordings of the mid-20th century, is it possible to go back to those days, now that digital layering and editing are part of the creative process? What is lost by removing the ‘imperfections’ of live performance in the mix?

The questions above are not new (indeed Robert Philip has posed these questions in the context of western art music record production), but through practice, our research project has shed some light on the hidden histories of Latin music production. I am an academic and a professional flute player, who specialises in Cuban charanga. Charanga is the name for a musical line-up of flute, violins, bass, piano, timbales, congas, güiro and vocalists which plays Latin dance styles, such as mambo, danzón, chachachá, pachanga and Cuban son. Its production history has not been documented in much detail to date. Through an experimental approach to recording Cuban charanga music, our research has tested out some hypotheses as to why more modern charanga recordings fail to compete with those produced in the 1950s and ‘60s.

Restaging historic recording set-ups

Our project investigates the performance aesthetics of Latin music in the recording studio and other live spaces using experimental archaeology. Employing tools and technologies as close as possible to those used in the past, the conditions of recording sessions from the 1950s and 1960s were restaged in order to explore particular aspects of the recording process not captured already by existing work. Ribbon microphone technology was used to record the 12-piece band Charanga del Norte and a ribbon microphone specialist from the company Xaudia provided additional microphones for the recordings. These experiments have helped to shed light on the benefits and problems of the live recording process and have provided findings which question how we narrate music history and, in particular, how we understand the production and performance history of vernacular non-Anglophone popular musics, which are consistently left out of accounts of music production history.

The introduction of ribbon microphone technologies and the introduction of magnetic tape in 1948 did not interfere too much with an ensemble’s performance dynamic, as the music was ‘shaped to tape’ by engineers during a live take. The room acoustics and microphone placements, with only mild compression applied in a three-to-one ratio during the recording, led to results that reflected what the musicians’ ears heard whilst they were playing live; thus the sound was less processed and less mediated. Modern multitrack digital approaches involve the use of more compression and other processing techniques added in post-production, where more control is given to the engineers and producers who edit, mix and master the final recordings.

Have more modern multitrack approaches led to a demise in musicianship skills?

Our recording experiment in a live space with no headphones enabled musicians to hear what their ears heard, although some players sought to reproduce the sounds of close miking in our live room ‘one-take experiments.’ For example, the conga player wanted to hear his slap strokes more clearly, so the one microphone for the whole rhythm section was moved nearer to his conga for the slap to come across more in playback. Unfortunately, this changed the dynamic balance of the three instruments for the ensuing takes; in the percussion section, the live dynamic entails the blending of the timbales with the güiro which would naturally sit higher in terms of volume than the congas. With the microphone moved closer to the congas, this internal balance was interfered with and the resultant subsequent recordings sounded less balanced. The güiro player similarly assumed reverb had been added to his sound when the reverb was the natural room acoustic. One could therefore put forward the idea that modern musicians have, to some degree, lost the ability to adapt to room size and acoustic due to the change in overall dynamic control, from musicians themselves to the sound engineers and producers.

Modern musicians have, to some degree, lost the ability to adapt to room size and acoustic due to the change in overall dynamic control, from musicians themselves to the sound engineers and producers.

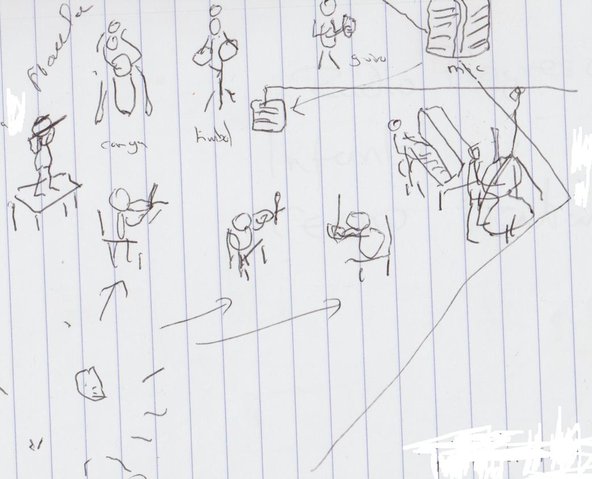

In the mid-20th century, much thought was given to placement of the double bass in the charanga orquesta. In this diagram, the bass player is placed in the corner to make use of natural amplification. Similarly, the flute player was often positioned in the centre of a horseshoe-shape arrangement, literally ‘holding the reins’ of the orquesta and dominating the sound. Recording in All Hallows Church in Hyde Park Leeds, the flute player was initially positioned on the altar, but the volume was considered too overpowering on the day. However the final recording was found not to have had the flute at the higher volume needed to meet the style’s aesthetic – again reflecting the 21st-century tastes of the musicians and recording engineers.

Today, most musicians expect amplification and internal dynamic balance to be sorted out technologically and perhaps do not realise how they could start to take back some of the control for dynamic levels for the whole ensemble. Relying on monitoring on stage instead of a natural balance of sounds can affect musicianship. Musicians today are perhaps, one could suggest, losing the ability to work together and adapt to room acoustics without overall amplification, whether in performance, rehearsal or in the studio. The mix of acoustic and electric instruments means a combination of approaches would be the ideal, but even players of acoustic instruments are used to hearing themselves through monitors, headphones or wireless in-ear monitors in live performance and studio settings even when performing live in an ensemble.

The ability to get everything down in one live take was also a higher priority in the mid-20th century. Modern day players know most things can be ‘fixed in the mix’ with multi-tracked approaches and, perhaps, now that regular live performances are less common, bands are less rehearsed before studio recording sessions take place. Internal balancing as a skill, although a focus in certain ensembles (e.g. a string quartet) has perhaps not been a focus in contemporary performance training and in recording situations for musicians.

The introduction of new technologies such as ribbon microphones was a turning point in musicians’ knowledge of room acoustics, where performance practices were enhanced rather than hindered as the live sound was captured on record with minimal processing. It was only with the introduction of multi-tracking that control of internal band dynamics came under the engineer and producer’s control. This transference of power to control balance and internal dynamics has affected the ways musicians themselves approach recording and also on the way they hear their music and perform it. Shaping the music to fit the venue is no longer thought about as much by musicians, although good sound engineers will almost always consider the room acoustics in their PA set-ups.

Spontaneity and control

Control of the dynamics of a recorded performance today is in the hands of the engineers, who nevertheless often work side by side with the musicians when mixing in the studio. The compressing and equalising of sounds changes a recording’s sound considerably and a recorded performance is almost always now ‘reconstructed’ from ‘live’ to ‘recorded’ and often back again, to emulate the sound of the initial live recording. Contemporary modes of recordings are more controlled than the live-take approach of the 1950s and ‘60s and the spontaneity captured in live-take recording is hard to replicate today with more highly processed and mediated approaches. Liveness as an aesthetic may be less prized today than before, although Latin clave-based dance music continues to have a live aesthetic. Many contemporary Latin bands still record as a live ensemble in one room to enable the spontaneity of ‘call and response’ to be recorded, albeit retaining the ability to overdub the singers who are often recorded in a booth with the ensemble but isolated from ‘bleed.’

Change does not always mean progress, and what one gains in control through multi-channel layering one loses in terms of spontaneity in ensemble performance. Certain aspects of musicianship are also lost as control for ensemble balance and dynamic changes hands from musician to engineer and even excellent professional musicians do not always adjust to their acoustic environment.

Dr Sue Miller is Reader in Music at Leeds Beckett University. She received a BA / Leverhulme Small Research Grant in 2018. Her research into capturing ‘liveness’ – experiments in the recording studio and live spaces is a collaborative project involving Dr Paul Thompson, sound engineers Barkley McKay and Michael Ward (from Leeds Beckett University ), industry specialists (Stuart Tavener of Xaudia), music documentary film maker Tim Blackwell and leading performers (Eddy Zervigón, Nestor Torres, and Sue’s band Charanga del Norte). The project featured in the British Academy Virtual Summer Showcase.

Further reading

Charanga Sue: project website

Creativity in the Recording Studio: Alternative Takes by Paul Thompson (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019)

Chasing Sound: Technology, Culture and the Art of Studio Recording from Edison to the LP, Susan Schmidt Horning (John Hopkins University Press, 2013)